People can’t seem to get enough of sparkling water these days. In fact, it exploded into a $29 billion global industry in 2020.1 With no calories or sweeteners, bubbly drinks like LaCroix, Bubly, and Hint may seem like healthy no-brainers.2 But are these sparkling waters actually good for you?

According to Sean Hashmi, MD, physician and regional director of weight management and clinical nutrition for Kaiser Permanente Southern California, there are a few things to keep in mind about your favorite sparkling drinks — particularly if they’re flavored.

Are sparkling waters healthy to drink?

Even though carbonated waters have zero calories, they aren’t necessarily healthy. To get its fizz, sparkling water is made by adding pressurized carbon dioxide into water. (Basically, how a SodaStream works.) This carbonation may, in fact, make you hungrier and cause you to eat more.

“One study found that carbon dioxide in drinks caused the hunger hormone ghrelin to shoot up, leading to overeating and weight gain in rats,” says Dr. Hashmi. In the same study, carbonated drinks also increased ghrelin levels in humans.3

But many other issues arise when flavor, like lemon or grapefruit, is added to sparkling water. “To add the fruity taste, these bubbly waters typically use artificial sweeteners like stevia, aspartame, and sucralose to make it sweet,” says Dr. Hashmi. It doesn’t matter if the sweeteners have zero calories or are made from a plant, he explains. “These artificial sweeteners are problematic because they are about 200 to 20,000 times sweeter than sugar.”

“When you drink something that’s 20,000 times sweeter than sugar, it may cause cravings for unhealthy sweets — which can be difficult to overcome,” says Dr. Hashmi. It can even change your taste buds, making naturally sweet foods taste different. “When you go to eat an apple or strawberries, these naturally sweet and delicious fruits don’t taste sweet anymore,” he explains.

Beyond that, zero-calorie artificial sweeteners may increase your risk for heart disease, weight gain, and other health issues, says Dr. Hashmi: “According to one study, people who consume higher amounts of artificial sweeteners, over several decades, have a dramatically higher risk of stroke and dementia.”4

Are “natural” sparkling water flavors healthier?

If you read the ingredients of most fruity carbonated waters, they likely list water and something like “natural flavors,” but no artificial sweeteners. That’s where things get complicated.

“The word ‘natural’ is a bit of a misnomer,” says Dr. Hashmi. “This is something the food industry uses to get us to buy products — and it makes my job very difficult because people think natural means healthy.”

The reality is that food chemists make “natural flavors” in a lab, re-creating specific tastes by extracting substances from plants or animals. That’s why they’re still labeled “natural.” Unlike squeezing a lemon wedge into your carbonated water, however, natural flavors are only meant for taste, not nutrition.5,6 But companies can use the catch-all term to make their ingredient list look simple and healthy.

Regardless of how it’s listed on the label, or whether the sweetener is made from a plant, these zero-calorie artificial sweeteners may not be good for your health.

What’s a healthier way to add flavor to water?

“At the end of the day, your good old plain water is still the absolute best drink for you,” says Dr. Hashmi. If you really must have it carbonated, he recommends plain carbonated water.

“If you want to add flavor to your water, add the fruit yourself,” Dr. Hashmi says. Put in lemons, limes, berries, whatever you like. The same goes for carbonated water. If you want flavor in your bubbles, add fruit to plain seltzer water.

And if it doesn’t taste as sweet as your go-to fruity sparkling water, just give it time. “You can change your taste buds in 7 to 10 days by changing what you eat,” says Dr. Hashmi. If you give up the artificial sweeteners for 7 to 10 days, the fruit will start to taste sweeter — and your water with strawberries will taste even better.

Bottom line: “Don’t rely on artificial sweeteners or sugar substitutes,” says Dr. Hashmi. “Nature is sweet enough as is.”

Thursday, July 29, 2021

Thursday, July 22, 2021

What’s in wildfire smoke? A toxicologist explains the health risks and which masks can help

Luke Montrose July 15, 2021 3.10pm EDT

Fire and health officials began issuing warnings about wildfire smoke several weeks earlier than normal this year. With almost the entire U.S. West in drought, signs already pointed to a long, dangerous fire season ahead.

Smoke is now turning the sky hazy across a large swath of the country as dozens of large fires burn, and a lot of people are wondering what’s in the air they’re breathing.

As an environmental toxicologist, I study the effects of wildfire smoke and how they differ from other sources of air pollution. We know that breathing wildfire smoke can be harmful. Less clear is what the worsening wildfire landscape will mean for public health in the future, but research is raising red flags.

In parts of the West, wildfire smoke now makes up nearly half the air pollution measured annually. A new study by the California Air Resources Board found another threat: high levels of lead and other metals turned up in smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise. The findings suggest smoke from fires that reach communities could be even more dangerous than originally thought because of the building materials that burn.

Fire and health officials began issuing warnings about wildfire smoke several weeks earlier than normal this year. With almost the entire U.S. West in drought, signs already pointed to a long, dangerous fire season ahead.

Smoke is now turning the sky hazy across a large swath of the country as dozens of large fires burn, and a lot of people are wondering what’s in the air they’re breathing.

As an environmental toxicologist, I study the effects of wildfire smoke and how they differ from other sources of air pollution. We know that breathing wildfire smoke can be harmful. Less clear is what the worsening wildfire landscape will mean for public health in the future, but research is raising red flags.

In parts of the West, wildfire smoke now makes up nearly half the air pollution measured annually. A new study by the California Air Resources Board found another threat: high levels of lead and other metals turned up in smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire, which destroyed the town of Paradise. The findings suggest smoke from fires that reach communities could be even more dangerous than originally thought because of the building materials that burn.

.

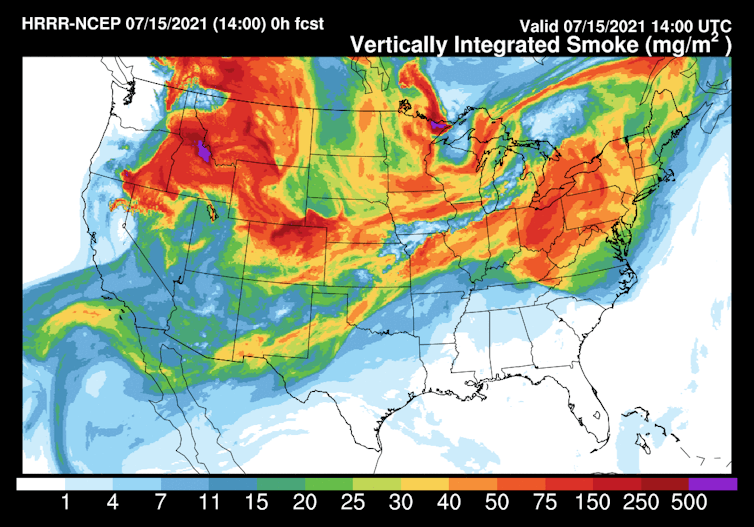

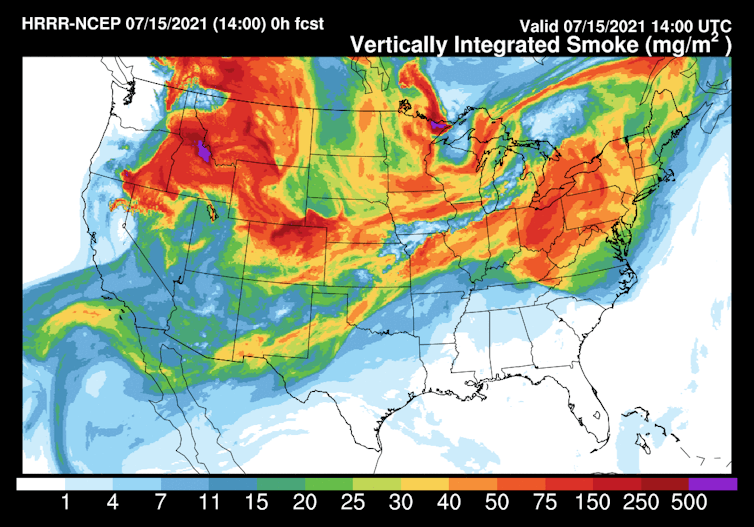

NOAA’s smoke forecast is based on where fires were burning on July 15, 2021. NOAA

Here’s a closer look at what makes up wildfire smoke and what you can do to protect yourself and your family.

What’s in wildfire smoke?

What exactly is in a wildfire’s smoke depends on a few key things: what’s burning – grass, brush or trees; the temperature – is it flaming or just smoldering; and the distance between the person breathing the smoke and the fire producing it.

The distance affects the ability of smoke to “age,” meaning to be acted upon by the Sun and other chemicals in the air as it travels. Aging can make it more toxic. Importantly, large particles like what most people think of as ash do not typically travel that far from the fire, but small particles, or aerosols, can travel across continents.

Smoke from wildfires contains thousands of individual compounds, including carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, carbon dioxide, hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides. The most prevalent pollutant by mass is particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, roughly 50 times smaller than a grain of sand. Its prevalence is one reason health authorities issue air quality warnings using PM 2.5 as the metric.

The new study on smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire found dangerous levels of lead in smoke blowing downwind as the fire burned through Paradise, California. The metals, which have been linked to health harms including high blood pressure and developmental effects in children with long-term exposure, traveled more than 150 miles on the wind, with concentrations 50 times above average in some areas.

What does that smoke do to human bodies?

There is another reason PM2.5 is used to make health recommendations: It defines the cutoff for particles that can travel deep into the lungs and cause the most damage.

The human body is equipped with natural defense mechanisms against particles bigger than PM2.5. As I tell my students, if you have ever coughed up phlegm or blown your nose after being around a campfire and discovered black or brown mucus in the tissue, you have witnessed these mechanisms firsthand.

The really small particles bypass these defenses and disturb the air sacs where oxygen crosses over into the blood. Fortunately, we have specialized immune cells present called macrophages. It’s their job to seek out foreign material and remove or destroy it. However, studies have shown that repeated exposure to elevated levels of wood smoke can suppress macrophages, leading to increases in lung inflammation.

Dose, frequency and duration are important when it comes to smoke exposure. Short-term exposure can irritate the eyes and throat. Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke over days or weeks, or breathing in heavy smoke, can raise the risk of lung damage and may also contribute to cardiovascular problems. Considering that it is the macrophage’s job to remove foreign material – including smoke particles and pathogens – it is reasonable to make a connection between smoke exposure and the risk of viral infection.

Recent evidence suggests that long-term exposure to PM2.5 may make the coronavirus more deadly. A nationwide study found that even a small increase in PM2.5 from one U.S. county to the next was associated with a large increase in the death rate from COVID-19.

What can you do to stay healthy?

Here’s the advice I would give

Here’s a closer look at what makes up wildfire smoke and what you can do to protect yourself and your family.

What’s in wildfire smoke?

What exactly is in a wildfire’s smoke depends on a few key things: what’s burning – grass, brush or trees; the temperature – is it flaming or just smoldering; and the distance between the person breathing the smoke and the fire producing it.

The distance affects the ability of smoke to “age,” meaning to be acted upon by the Sun and other chemicals in the air as it travels. Aging can make it more toxic. Importantly, large particles like what most people think of as ash do not typically travel that far from the fire, but small particles, or aerosols, can travel across continents.

Smoke from wildfires contains thousands of individual compounds, including carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, carbon dioxide, hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides. The most prevalent pollutant by mass is particulate matter less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, roughly 50 times smaller than a grain of sand. Its prevalence is one reason health authorities issue air quality warnings using PM 2.5 as the metric.

The new study on smoke from the 2018 Camp Fire found dangerous levels of lead in smoke blowing downwind as the fire burned through Paradise, California. The metals, which have been linked to health harms including high blood pressure and developmental effects in children with long-term exposure, traveled more than 150 miles on the wind, with concentrations 50 times above average in some areas.

What does that smoke do to human bodies?

There is another reason PM2.5 is used to make health recommendations: It defines the cutoff for particles that can travel deep into the lungs and cause the most damage.

The human body is equipped with natural defense mechanisms against particles bigger than PM2.5. As I tell my students, if you have ever coughed up phlegm or blown your nose after being around a campfire and discovered black or brown mucus in the tissue, you have witnessed these mechanisms firsthand.

The really small particles bypass these defenses and disturb the air sacs where oxygen crosses over into the blood. Fortunately, we have specialized immune cells present called macrophages. It’s their job to seek out foreign material and remove or destroy it. However, studies have shown that repeated exposure to elevated levels of wood smoke can suppress macrophages, leading to increases in lung inflammation.

Dose, frequency and duration are important when it comes to smoke exposure. Short-term exposure can irritate the eyes and throat. Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke over days or weeks, or breathing in heavy smoke, can raise the risk of lung damage and may also contribute to cardiovascular problems. Considering that it is the macrophage’s job to remove foreign material – including smoke particles and pathogens – it is reasonable to make a connection between smoke exposure and the risk of viral infection.

Recent evidence suggests that long-term exposure to PM2.5 may make the coronavirus more deadly. A nationwide study found that even a small increase in PM2.5 from one U.S. county to the next was associated with a large increase in the death rate from COVID-19.

What can you do to stay healthy?

Here’s the advice I would give

e just about anyone downwind from a wildfire.

Stay informed about air quality by identifying local resources for air quality alerts, information about active fires and recommendations for better health practices.

If possible, avoid being outside or doing strenuous activity, like running or cycling, when there is an air quality warning for your area.

Stay informed about air quality by identifying local resources for air quality alerts, information about active fires and recommendations for better health practices.

If possible, avoid being outside or doing strenuous activity, like running or cycling, when there is an air quality warning for your area.

Wildfire smoke pours over palm trees lining a street in Azusa, California, on Aug. 13, 2020. AP Images/Marcio Jose Sanchez

Be aware that not all face masks protect against smoke particles. Most cloth masks will not capture small wood smoke particles. That requires an N95 mask that fits and is worn properly. Without a proper fit, N95s do not work as well.

Establish a clean space. Some communities in western states have offered “clean spaces” programs that help people take refuge in buildings with clean air and air conditioning. However, during the pandemic, being in an enclosed space with others can create other health risks. At home, a person can create clean and cool spaces using a window air conditioner and a portable air purifier.

The Environmental Protection Agency also advises people to avoid anything that contributes to indoor air pollutants. That includes vacuuming that can stir up pollutants, as well as burning candles, firing up gas stoves and smoking.

Be aware that not all face masks protect against smoke particles. Most cloth masks will not capture small wood smoke particles. That requires an N95 mask that fits and is worn properly. Without a proper fit, N95s do not work as well.

Establish a clean space. Some communities in western states have offered “clean spaces” programs that help people take refuge in buildings with clean air and air conditioning. However, during the pandemic, being in an enclosed space with others can create other health risks. At home, a person can create clean and cool spaces using a window air conditioner and a portable air purifier.

The Environmental Protection Agency also advises people to avoid anything that contributes to indoor air pollutants. That includes vacuuming that can stir up pollutants, as well as burning candles, firing up gas stoves and smoking.

Saturday, July 17, 2021

Still Doubting the efficacy of the Vaccine?

From an astute and well-educated friend:

To all my otherwise very intelligent friends and family, who do not trust the coronavirus vaccines. I fully understand that you truly believe what you are thinking and, in some cases, have found sites and authorities that support your beliefs. I would ordinarily just shrug and say the outcome is Darwinian, except that, especially my family, I treasure you too much not to make an effort to convince you. Younger people do not just “pass-through” this disease with relatively minor discomfort. The Delta variant is killing younger folks at an alarming rate, particularly conservatives in southern states. Older people who have received the vaccines are not dying or even being hospitalized. Those are not made-up statistics. I am conservative, received my second Pfizer shot last February and I am very much still alive. If a booster shot is needed, I will be first in line for it. Please consider this!

The vaccine is safe.

Hello, there has been a lot of misinformation concerning the development of the SARS-Cov-2 vaccine developed by Pfizer and Moderna. I just went online and asked a simple question, " when was MRNA discovered"? Here are the facts and I hope those who think that this science is not safe to go online and do a little due diligence. 1961. mRNA is discovered at Cal Tech. Research has been ongoing for Sixty years in this subject. Moving on to the pandemic, it appears there was some luck involved in getting this vaccine out as quickly as it happened.

A. A lot of research was already in the pipeline concerning similar respiratory viruses. Scientists were NOT starting from scratch.

B. The federal government addressed the time-consuming processes of the trial setup, funding, etc. These processes were streamlined for efficiency savings.

C. Luck. SARS-Cov-2 is not complicated when compared to HIV or Dengue virus. Scientists sequenced the genetic code quickly. They plugged it into an experimental system already developed for other viruses, including Respiratory Syncytial Viruses ( RSV). This system was created more than a decade ago. Most vaccines use a weakened virus which takes much longer to process. That is why the quickest vaccine to date took four years to develop. These vaccines are genetically derived and the time period was much less to develop. Add to that the huge government funding and the science community dropping most everything else to work on this one project and the time period to develop these vaccines was incredibly shortened. Clinical trials are still underway as there is only an " emergency use " approval so far. But all data suggests that this is a safe vaccine as hundreds of millions of people have taken at least one does this far. Scientists expect full approval soon.

Finally, the latest data from the CDC is that 99.2% of all new cases of covid are those who have not been vaccinated. The latest variant of this virus is a more infectious and deadly strain and I leave it to all those who are resisting getting vaccinated to think long and hard on this. Please just type in a question about these vaccines and read up on the real facts, not opinions on ND.

To all my otherwise very intelligent friends and family, who do not trust the coronavirus vaccines. I fully understand that you truly believe what you are thinking and, in some cases, have found sites and authorities that support your beliefs. I would ordinarily just shrug and say the outcome is Darwinian, except that, especially my family, I treasure you too much not to make an effort to convince you. Younger people do not just “pass-through” this disease with relatively minor discomfort. The Delta variant is killing younger folks at an alarming rate, particularly conservatives in southern states. Older people who have received the vaccines are not dying or even being hospitalized. Those are not made-up statistics. I am conservative, received my second Pfizer shot last February and I am very much still alive. If a booster shot is needed, I will be first in line for it. Please consider this!

The vaccine is safe.

Hello, there has been a lot of misinformation concerning the development of the SARS-Cov-2 vaccine developed by Pfizer and Moderna. I just went online and asked a simple question, " when was MRNA discovered"? Here are the facts and I hope those who think that this science is not safe to go online and do a little due diligence. 1961. mRNA is discovered at Cal Tech. Research has been ongoing for Sixty years in this subject. Moving on to the pandemic, it appears there was some luck involved in getting this vaccine out as quickly as it happened.

A. A lot of research was already in the pipeline concerning similar respiratory viruses. Scientists were NOT starting from scratch.

B. The federal government addressed the time-consuming processes of the trial setup, funding, etc. These processes were streamlined for efficiency savings.

C. Luck. SARS-Cov-2 is not complicated when compared to HIV or Dengue virus. Scientists sequenced the genetic code quickly. They plugged it into an experimental system already developed for other viruses, including Respiratory Syncytial Viruses ( RSV). This system was created more than a decade ago. Most vaccines use a weakened virus which takes much longer to process. That is why the quickest vaccine to date took four years to develop. These vaccines are genetically derived and the time period was much less to develop. Add to that the huge government funding and the science community dropping most everything else to work on this one project and the time period to develop these vaccines was incredibly shortened. Clinical trials are still underway as there is only an " emergency use " approval so far. But all data suggests that this is a safe vaccine as hundreds of millions of people have taken at least one does this far. Scientists expect full approval soon.

Finally, the latest data from the CDC is that 99.2% of all new cases of covid are those who have not been vaccinated. The latest variant of this virus is a more infectious and deadly strain and I leave it to all those who are resisting getting vaccinated to think long and hard on this. Please just type in a question about these vaccines and read up on the real facts, not opinions on ND.

Saturday, July 10, 2021

An Unlikely Hero: the Marine who found two WTC survivors

Rebecca Liss- September 11, 2015

(I came across this story- remembering having heard it many years ago. A longer read- but well worth it.)

Dave Karnes

Dave Karnes

Photo courtesy Marines magazine/Department of Defense

On the first anniversary of 9/11, with the attacks still fresh in the minds of many Americans, Slate shared the story of a retired Marine who responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center and found two survivors. In honor of the anniversary, the article is reprinted below.

Only 12 survivors were pulled from the rubble of the World Trade Center after the towers fell on Sept. 11, 2001, despite intense rescue efforts. Two of the last three to be located and saved were Port Authority police officers. They were not discovered by a heroic firefighter, or a rescue worker, or a cop. They were discovered by Dave Karnes.

Karnes hadn’t been near the World Trade Center. He wasn’t even in New York when the planes hit the towers. He was in Wilton, Conn., working in his job as a senior accountant with Deloitte Touche. When the second plane hit, Karnes told his colleagues, “We’re at war.” He had spent 23 years in the Marine Corps infantry and felt it was his duty to help. Karnes told his boss he might not see him for a while.

Then he went to get a haircut.

The small barbershop in Stamford, Conn., near his home, was deserted. “Give me a good Marine Corps squared-off haircut,” he told the barber. When it was done, he drove home to put on his uniform. Karnes always kept two sets of Marine fatigues hanging in his closet, pressed and starched. “It’s kind of weird to do, but it comes in handy,” he says. Next Karnes stopped by the storage facility where he kept his equipment—he’d need rappelling gear, ropes, canteens of water, his Marine Corps K-Bar knife, and a flashlight, at least. Then he drove to church. He asked the pastor and parishioners to say a prayer that God would lead him to survivors. A devout Christian, Karnes often turned to God when faced with decisions.

Finally, Karnes lowered the convertible top on his Porsche. This would make it easier for the authorities to look in and see a Marine, he reasoned. If they could see who he was, he’d be able to zip past checkpoints and more easily gain access to the site. For Karnes, it was a “God thing” that he was in the Porsche—a Porsche 911—that day. He’d only purchased it a month earlier—it had been a stretch, financially. But he decided to buy it after his pastor suggested that he “pray on it.” He had no choice but to take it that day because his Mercury was in the shop. Driving the Porsche at speeds of up to 120 miles per hour, he reached Manhattan—after stopping at McDonald’s for a hamburger—in the late afternoon.

His plan worked. With the top off, the cops could see his pressed fatigues, his neatly cropped hair, and his gear up front. They waved him past the barricades. He arrived at the site—“the pile”—at about 5:30. Building 7 of the World Trade Center, a 47-story office structure adjacent to the fallen twin towers, had just dramatically collapsed. Rescue workers had been ordered off the pile—it was too unsafe to let them continue. Flames were bursting from a number of buildings, and the whole site was considered unstable. Standing on the edge of the burning pile, Karnes spotted … another Marine dressed in camouflage. His name was Sgt. Thomas. Karnes never learned his first name, and he’s never come forward in the time since.

Together Karnes and Thomas walked around the pile looking for a point of entry farther from the burning buildings. They also wanted to move away from officials trying to keep rescue workers off the pile. Thick, black smoke blanketed the site. The two Marines couldn’t see where to enter. But then “the smoke just opened up.” The sun was setting and through the opening Karnes, for the first time, saw clearly the massive destruction. “I just said ‘Oh, my God, it’s totally gone.’ ” With the sudden parting of the smoke, Karnes and Thomas entered the pile. “We just disappeared into the smoke—and we ran.”

They climbed over the tangled steel and began looking into voids. They saw no one else searching the pile—the rescue workers having obeyed the order to leave the area. “United States Marines,” Karnes began shouting. “If you can hear us, yell or tap!”

Over and over, Karnes shouted the words. Then he would pause and listen. Debris was shifting and parts of the building were collapsing further. Fires burned all around. “I just had a sense, an overwhelming sense come over me that we were walking on hallowed ground, that tens of thousands of people could be trapped and dead beneath us,” he said.

After about an hour of searching and yelling, Karnes stopped.

“Be quiet,” he told Thomas, “I think I can hear something.”

He yelled again. “We can hear you. Yell louder.” He heard a faint muffled sound in the distance.

“Keep yelling. We can hear you.” Karnes and Thomas zeroed in on the sound.

“We’re over here,” they heard.

Two Port Authority police officers, Will Jimeno and Sgt. John McLoughlin were buried in the center of the World Trade Center ruins, 20 feet below the surface. They could be heard but not seen. By jumping into a larger opening, Karnes could hear Jimeno better. But he still couldn’t see him. Karnes sent Thomas to look for help. Then he used his cellphone to call his wife, Rosemary, in Stamford and his sister Joy in Pittsburgh. (He thought they could work the phones and get through to New York Police Department headquarters.)

“Don’t leave us,” Jimeno pleaded. He later said he feared Karnes’ voice would trail away, as had that of another potential rescuer hours earlier. It was now about 7 p.m. and Jimeno and McLoughlin had been trapped for roughly nine hours. Karnes stayed with them, talking to them until help arrived, in the form of Chuck Sereika, a former paramedic with an expired license who put pulled his old uniform out of his closet and came to the site. Ten minutes later, Scott Strauss and Paddy McGee, officers with the elite Emergency Service Unit of the NYPD, also arrived.

The story of how Strauss and Sereika spent three hours digging Jimeno out of the debris, which constantly threatened to collapse, has been well told in the New York Times and elsewhere. At one point, all they had with which to dig out Jimeno were a pair of handcuffs. Karnes stood by, helping pass tools to Strauss, offering his Marine K-Bar knife when it looked as if they might have to amputate Jimeno’s leg to free him. (After Jimeno was finally pulled out, another team of cops worked for six more hours to free McLoughlin, who was buried deeper in the pile.)

Karnes left the site that night when Jimeno was rescued and went with him to the hospital. While doctors treated the injured cop, Karnes grabbed a few hour's sleep on an empty bed in the hospital psychiatric ward. While he slept, the hospital cleaned and pressed his uniform.

* * *

Today, on the anniversary of the attack and the rescue, officers Jimeno and Strauss will be part of the formal “Top Cop” ceremony at the New York City Center Theater. Earlier the two appeared on a nationally televised episode of America’s Most Wanted. Jimeno and McLoughlin appeared this week on the Today show. They are heroes.

Today, Dave Karnes will be speaking at the Maranatha Bible Baptist Church in Wilkinsburg, Pa., near where he grew up. He sounds excited, over the phone, talking about the upcoming ceremony. Karnes is a hero, too.

But it’s also clear Karnes is a hero in a smaller, less national, less public, less publicized way than the cops and firefighters are heroes. He’s hardly been overlooked—the program I work for, 60 Minutes II, interviewed him as part of a piece on Jimeno’s rescue—but the great televised glory machine has so far not picked him. Why? One reason seems obvious—the cops and firefighters are part of big, respected, institutional support networks. Americans are grateful for the sacrifices their entire organizations made a year ago. Plus, the police and firefighting institutions are tribal brotherhoods. The firefighters help and support and console each other; the cops do the same. They find it harder to make room for outsiders like Karnes (or Chuck Sereika). And, it must be said, at some macho level it’s vaguely embarrassing that the professional rescuers weren’t the ones who found the two survivors. While the pros were pulled back out of legitimate caution, the job fell to an outsider, who drove down from Connecticut and just walked onto the burning pile.

Columnist Stewart Alsop once famously identified two rare types of soldiers, the “crazy brave” and the “phony tough.” The professionals at Ground Zero—I interviewed dozens in my work as a producer for CBS—were in no way phony toughs. But Karnes does seem a bit “crazy brave.” You’d have to be slightly abnormal—abnormally selfless, abnormally patriotic—to do what he did. And some of the same qualities that led Karnes to make himself a hero when it counted may make him less perfect as the image of a hero today.

Strauss tells a story that gets at this. When he was out on the pile a year ago, trying to pull Jimeno free, Strauss shouted orders to his volunteer helpers—“Medic, I need air,” or “Marine, get me some water.” At one point, in the middle of this exhausting work, Strauss, asked if he could call them by their names to facilitate the process. The medic said he was “Chuck.”

Karnes said: “You can call me ‘staff sergeant.’ “

“That’s three syllables!” said Strauss, who needed every bit of energy and every second of time. “Isn’t there something shorter?”

Karnes replied: “You can call me ‘staff sergeant.’ “

(I came across this story- remembering having heard it many years ago. A longer read- but well worth it.)

Dave Karnes

Dave KarnesPhoto courtesy Marines magazine/Department of Defense

On the first anniversary of 9/11, with the attacks still fresh in the minds of many Americans, Slate shared the story of a retired Marine who responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center and found two survivors. In honor of the anniversary, the article is reprinted below.

Only 12 survivors were pulled from the rubble of the World Trade Center after the towers fell on Sept. 11, 2001, despite intense rescue efforts. Two of the last three to be located and saved were Port Authority police officers. They were not discovered by a heroic firefighter, or a rescue worker, or a cop. They were discovered by Dave Karnes.

Karnes hadn’t been near the World Trade Center. He wasn’t even in New York when the planes hit the towers. He was in Wilton, Conn., working in his job as a senior accountant with Deloitte Touche. When the second plane hit, Karnes told his colleagues, “We’re at war.” He had spent 23 years in the Marine Corps infantry and felt it was his duty to help. Karnes told his boss he might not see him for a while.

Then he went to get a haircut.

The small barbershop in Stamford, Conn., near his home, was deserted. “Give me a good Marine Corps squared-off haircut,” he told the barber. When it was done, he drove home to put on his uniform. Karnes always kept two sets of Marine fatigues hanging in his closet, pressed and starched. “It’s kind of weird to do, but it comes in handy,” he says. Next Karnes stopped by the storage facility where he kept his equipment—he’d need rappelling gear, ropes, canteens of water, his Marine Corps K-Bar knife, and a flashlight, at least. Then he drove to church. He asked the pastor and parishioners to say a prayer that God would lead him to survivors. A devout Christian, Karnes often turned to God when faced with decisions.

Finally, Karnes lowered the convertible top on his Porsche. This would make it easier for the authorities to look in and see a Marine, he reasoned. If they could see who he was, he’d be able to zip past checkpoints and more easily gain access to the site. For Karnes, it was a “God thing” that he was in the Porsche—a Porsche 911—that day. He’d only purchased it a month earlier—it had been a stretch, financially. But he decided to buy it after his pastor suggested that he “pray on it.” He had no choice but to take it that day because his Mercury was in the shop. Driving the Porsche at speeds of up to 120 miles per hour, he reached Manhattan—after stopping at McDonald’s for a hamburger—in the late afternoon.

His plan worked. With the top off, the cops could see his pressed fatigues, his neatly cropped hair, and his gear up front. They waved him past the barricades. He arrived at the site—“the pile”—at about 5:30. Building 7 of the World Trade Center, a 47-story office structure adjacent to the fallen twin towers, had just dramatically collapsed. Rescue workers had been ordered off the pile—it was too unsafe to let them continue. Flames were bursting from a number of buildings, and the whole site was considered unstable. Standing on the edge of the burning pile, Karnes spotted … another Marine dressed in camouflage. His name was Sgt. Thomas. Karnes never learned his first name, and he’s never come forward in the time since.

Together Karnes and Thomas walked around the pile looking for a point of entry farther from the burning buildings. They also wanted to move away from officials trying to keep rescue workers off the pile. Thick, black smoke blanketed the site. The two Marines couldn’t see where to enter. But then “the smoke just opened up.” The sun was setting and through the opening Karnes, for the first time, saw clearly the massive destruction. “I just said ‘Oh, my God, it’s totally gone.’ ” With the sudden parting of the smoke, Karnes and Thomas entered the pile. “We just disappeared into the smoke—and we ran.”

They climbed over the tangled steel and began looking into voids. They saw no one else searching the pile—the rescue workers having obeyed the order to leave the area. “United States Marines,” Karnes began shouting. “If you can hear us, yell or tap!”

Over and over, Karnes shouted the words. Then he would pause and listen. Debris was shifting and parts of the building were collapsing further. Fires burned all around. “I just had a sense, an overwhelming sense come over me that we were walking on hallowed ground, that tens of thousands of people could be trapped and dead beneath us,” he said.

After about an hour of searching and yelling, Karnes stopped.

“Be quiet,” he told Thomas, “I think I can hear something.”

He yelled again. “We can hear you. Yell louder.” He heard a faint muffled sound in the distance.

“Keep yelling. We can hear you.” Karnes and Thomas zeroed in on the sound.

“We’re over here,” they heard.

Two Port Authority police officers, Will Jimeno and Sgt. John McLoughlin were buried in the center of the World Trade Center ruins, 20 feet below the surface. They could be heard but not seen. By jumping into a larger opening, Karnes could hear Jimeno better. But he still couldn’t see him. Karnes sent Thomas to look for help. Then he used his cellphone to call his wife, Rosemary, in Stamford and his sister Joy in Pittsburgh. (He thought they could work the phones and get through to New York Police Department headquarters.)

“Don’t leave us,” Jimeno pleaded. He later said he feared Karnes’ voice would trail away, as had that of another potential rescuer hours earlier. It was now about 7 p.m. and Jimeno and McLoughlin had been trapped for roughly nine hours. Karnes stayed with them, talking to them until help arrived, in the form of Chuck Sereika, a former paramedic with an expired license who put pulled his old uniform out of his closet and came to the site. Ten minutes later, Scott Strauss and Paddy McGee, officers with the elite Emergency Service Unit of the NYPD, also arrived.

The story of how Strauss and Sereika spent three hours digging Jimeno out of the debris, which constantly threatened to collapse, has been well told in the New York Times and elsewhere. At one point, all they had with which to dig out Jimeno were a pair of handcuffs. Karnes stood by, helping pass tools to Strauss, offering his Marine K-Bar knife when it looked as if they might have to amputate Jimeno’s leg to free him. (After Jimeno was finally pulled out, another team of cops worked for six more hours to free McLoughlin, who was buried deeper in the pile.)

Karnes left the site that night when Jimeno was rescued and went with him to the hospital. While doctors treated the injured cop, Karnes grabbed a few hour's sleep on an empty bed in the hospital psychiatric ward. While he slept, the hospital cleaned and pressed his uniform.

* * *

Today, on the anniversary of the attack and the rescue, officers Jimeno and Strauss will be part of the formal “Top Cop” ceremony at the New York City Center Theater. Earlier the two appeared on a nationally televised episode of America’s Most Wanted. Jimeno and McLoughlin appeared this week on the Today show. They are heroes.

Today, Dave Karnes will be speaking at the Maranatha Bible Baptist Church in Wilkinsburg, Pa., near where he grew up. He sounds excited, over the phone, talking about the upcoming ceremony. Karnes is a hero, too.

But it’s also clear Karnes is a hero in a smaller, less national, less public, less publicized way than the cops and firefighters are heroes. He’s hardly been overlooked—the program I work for, 60 Minutes II, interviewed him as part of a piece on Jimeno’s rescue—but the great televised glory machine has so far not picked him. Why? One reason seems obvious—the cops and firefighters are part of big, respected, institutional support networks. Americans are grateful for the sacrifices their entire organizations made a year ago. Plus, the police and firefighting institutions are tribal brotherhoods. The firefighters help and support and console each other; the cops do the same. They find it harder to make room for outsiders like Karnes (or Chuck Sereika). And, it must be said, at some macho level it’s vaguely embarrassing that the professional rescuers weren’t the ones who found the two survivors. While the pros were pulled back out of legitimate caution, the job fell to an outsider, who drove down from Connecticut and just walked onto the burning pile.

Columnist Stewart Alsop once famously identified two rare types of soldiers, the “crazy brave” and the “phony tough.” The professionals at Ground Zero—I interviewed dozens in my work as a producer for CBS—were in no way phony toughs. But Karnes does seem a bit “crazy brave.” You’d have to be slightly abnormal—abnormally selfless, abnormally patriotic—to do what he did. And some of the same qualities that led Karnes to make himself a hero when it counted may make him less perfect as the image of a hero today.

Strauss tells a story that gets at this. When he was out on the pile a year ago, trying to pull Jimeno free, Strauss shouted orders to his volunteer helpers—“Medic, I need air,” or “Marine, get me some water.” At one point, in the middle of this exhausting work, Strauss, asked if he could call them by their names to facilitate the process. The medic said he was “Chuck.”

Karnes said: “You can call me ‘staff sergeant.’ “

“That’s three syllables!” said Strauss, who needed every bit of energy and every second of time. “Isn’t there something shorter?”

Karnes replied: “You can call me ‘staff sergeant.’ “

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)